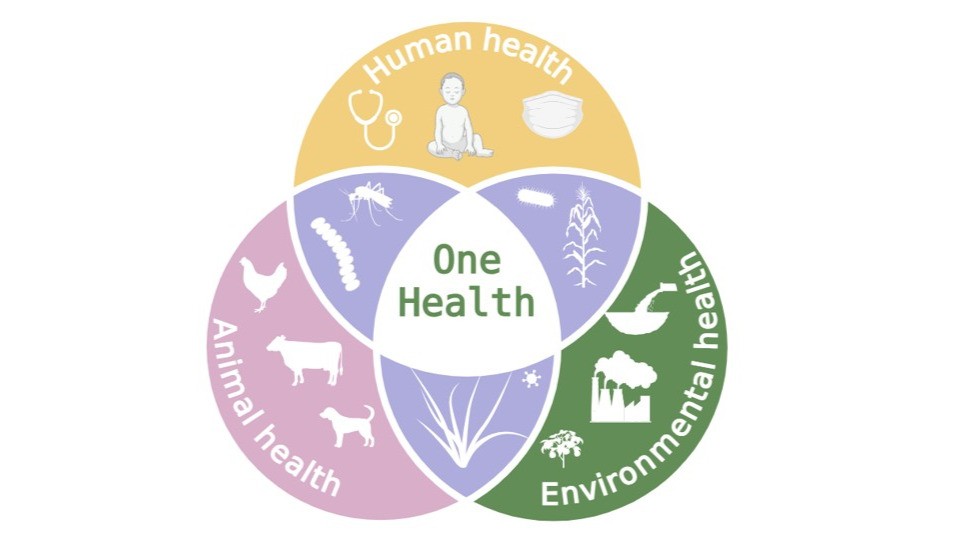

Every year, on Nov. 3, the world observes One Health Day, commemorating a collaborative approach that acknowledges the interconnectedness among human, animal, and environmental health.

The One Health approach promotes cross-sector collaboration to prevent, detect, and respond to health threats at this interface, because no sector can safeguard health alone.

In Nigeria, the One Health vision took shape with the National One Health Strategic Plan (2019–2023), jointly developed by the Federal Ministries of Health, Agriculture, and Environment, alongside partners like the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC) and academia.

The plan is aimed at strengthening surveillance, coordination, and food safety through multi-sectoral collaboration.

However, six years later, experts say that while policy frameworks exist, the reality on the ground still reflects a broken chain, where weak veterinary systems, poor environmental management, and limited intersectoral coordination continue to expose Nigerians to preventable diseases and economic losses.

In her quiet home in Kabusa, Abuja, poultry farmer, Mrs Ruth Yusuf, recounts how a mysterious disease wiped out her entire flock.

No veterinarian came to investigate, and local laboratories lacked the capacity to test her samples.

Within weeks, her family fell ill, a grim reminder that in Nigeria, animal health and human health remain dangerously intertwined.

Experts say this underscores the need to operationalise the One Health approach at every level.

More than 70 per cent of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic, originating in animals before spreading to humans.

Records also show that more than 75 per cent of emerging infectious diseases in humans originate from animals.

In Nigeria, zoonotic diseases like rabies, Lassa fever, and avian influenza remain major public health threats due to weak surveillance and poor data systems.

Outbreaks of Lassa fever, avian influenza, anthrax, and monkeypox highlight the dangers of neglecting the link between animals and the environment.

A Virologist, Dr Solomon Chollom, warned that “every time we fail to control an infection in livestock or wildlife, we create the next potential public health emergency”.

Chollom explained that early detection in animals was cheaper and safer than responding after human infections occur.

Livestock form the backbone of rural livelihoods. When animals fall ill, entire households collapse economically.

According to the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, livestock diseases cost Nigeria billions of naira annually in lost productivity.

Livestock diseases continue to drain Nigeria’s economy, deepening poverty and food insecurity.

Experts say bridging the One Health resource gap, through stronger funding, infrastructure, and vaccination is key to preventing future outbreaks. Dr Grace Olaoye, a veterinary epidemiologist, notes that “economic resilience in rural Nigeria depends on animal health. You cannot fight poverty without healthy herds.”

Olaoye said that without compensation or insurance schemes, farmers shoulder losses alone, pushing more families into poverty and deepening food insecurity, especially among women engaged in small-scale poultry and dairy farming.

Dr Fatai Abubakar of the Nigerian Infectious Diseases Society calls antimicrobial resistance (AMR) a “silent epidemic.”

Abubakar said that farmers frequently purchased antibiotics over the counter and added them to animal feed without guidance, driving the emergence of resistant bacteria.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) ranks AMR among the world’s top 10 health threats, and Nigeria records tens of thou- sands of deaths yearly from drug-resistant infections.

“Without strong veterinary oversight, resistant bacteria will continue to move from farms to food and to hospitals.